Virtual Dilemma: A Call for a New Curatorial Aesthetic

by Jackson Larson, UNMAM Research Assistant and UNM PhD Candidate in Art History

In 2020, everything changed. Museum exhibitions were no exception. What once took place in the gallery was pushed online. As museum doors around the world were closed, many museum curators and exhibition designers turned to virtual exhibitions as a stop-gap measure. The tools of the trade changed overnight. Hammers and nails were replaced by pixels and code. But new tools require new skills, and new skills don’t always come easily. Such was the case as the UNMAM museum staff attempted to create an online version of the permanent collection exhibition. After much investigation, exhibitions coordinator Steven Hurley found the software to make our exhibitions virtual, and began the process by creating a 360° photo of the gallery. However, curator Mary Statzer and I found early versions of our virtual exhibition lacking a human touch. So, we decided to create videos of ourselves speaking about the artworks to enhance the experience.

It was a classic case of our vision outreaching our skills. There we sat, in an empty gallery, an i-Phone strapped to a tripod with a rubber band, trying to remember our lines. We attempted panning shots with rolling office chairs and used our feeble knowledge of video software to edit out the deafening HVAC fan in the gallery. However, we could not ignore the fact that we were not filmmakers. We had neither the equipment nor the knowledge, but we had high standards, and in service of them, we had to become filmmakers overnight. Not only that, we also had to become actors. It is a strange phenomenon, but the camera renders the average person mute. Just the knowledge of being recorded seems to make one unable to string a single sentence together. Twenty-four attempts later, without a single usable take, our priorities changed. Our grand ideations of eloquence, charm, and good hair were replaced by the humble hope that we would be able to spit out our lines without stuttering or running out of cloud storage. We told ourselves that the shaky shots and fumbled lines were charming but the perfectionists in us worried. Should we just give up?

But we had to do something. Without a little something extra, a virtual exhibit is just a bad video game⏤a digital Easter egg hunt without any eggs. A virtual exhibit is nothing like a real exhibit. For me, the poetry is gone. Curators arrange art like poets arrange words. Changing placement of the work changes the story. The electricity and meaning generated between works is where the true magic lies. While ostensibly a reproduction of the real thing, virtual exhibits are jerky and distorted. It’s difficult to get one’s bearings, and impossible to see sculptures from more than one angle. Even paintings and drawings lose their subtle physical properties. The tooth of the paper and strokes of the brush are lost in translation. This is not the way the artists intended their work to be experienced. Furthermore, if you thought museums were quiet, it’s nothing compared to the uncanny silence of a virtual exhibition. When the hushed murmuring of museum visitors and squeaking of shoes in the gallery are replaced by the sterile hum of your computer fan you become painfully aware of the absence. Despite the enormous effort involved in creating this digital replica, we were in danger of doing a disservice to the art and the museum experience.

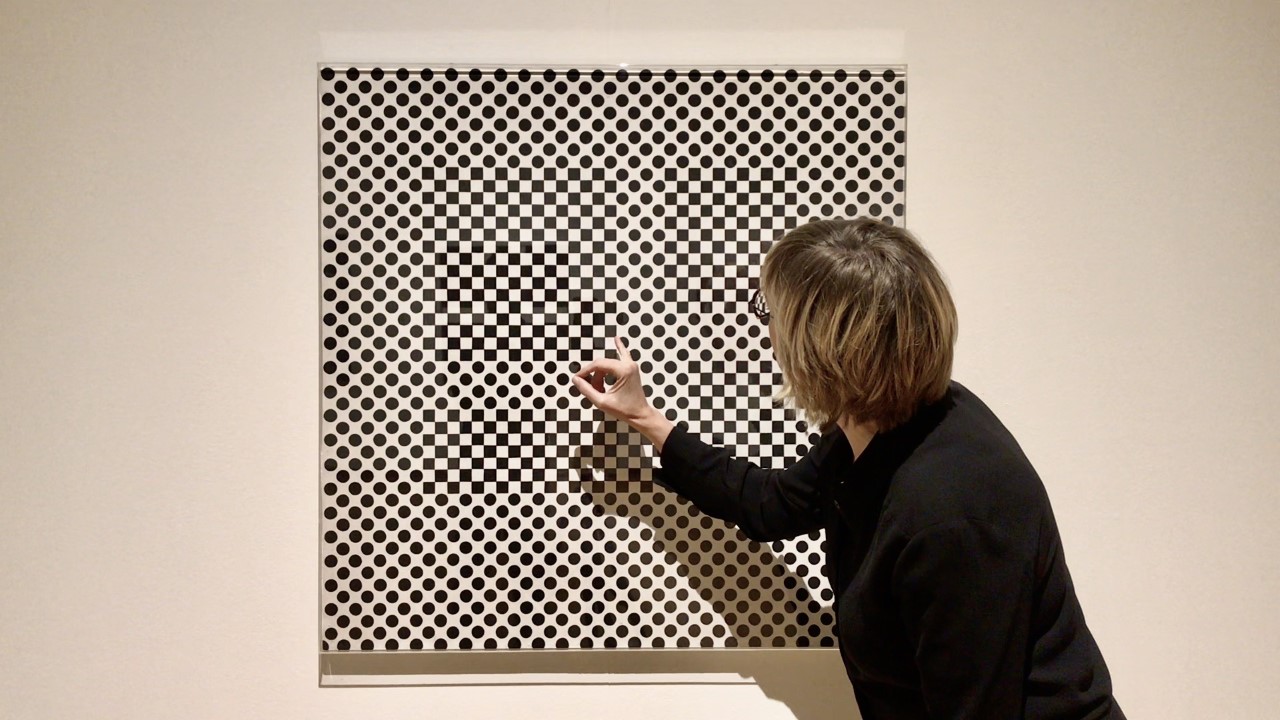

Video had the potential to make up for some of these deficiencies. It allows one to see the work a little closer to the way it was intended, from different angles and with a sense of scale. Video adds sound and motion. Perhaps most importantly, video shows humans interacting with the art. This human element also reminds people of the all the humans involved in making both the art and the exhibit possible. Art does not just magically appear on a wall or even online, it is the product of great knowledge, training, and expertise, not to mention financial investment. The ghostly virtual format, with its unnerving panoptic view of the gallery makes this easy to forget. While video allowed us to show some of the humans involved, it also made it more difficult to edit out their flaws. In the end, we opted for humanity over perfection. Perfection is so 2019. This new moment calls for a new aesthetic, one that is nimble enough to embrace these new challenges. Perhaps we can take a page from the punk DIY filmmakers of the 20th century who reveled in the novelty and rawness of video technology. Like those rebellious artists before us, I look forward to seeing how today’s curators rebel against the constraints of the digital space.

Hindsight/Insight first opened at the UNM Art Museum in 2018, with a new rotation of artwork introduced in 2019. The exhibition highlights over 30 artworks acquired since the museum’s founding and celebrates the teaching collection developed for the University community. This virtual iteration of the exhibition creates an expanded experience with the addition of video commentaries by museum staff.