Students Reflect on ‘Evolving Visions’

Students from 20th Century Photography, a class taught by UNM Assistant Professor of Art History, Kevin Mulhearn, were asked to write reflections on artworks from the section ‘Evolving Visions: 20th Century Photography’ in Hindsight Insight 3.0: Portraits, Landscapes, and Abstraction from the UNM Art Museum. UNMAM Curator of Prints & Photographs, Mary Statzer, led students on a tour of the exhibition exploring the section’s historical context and its meaning within Hindsight Insight 3.0.

The goal of this project is to feature student voices in the museum. Below are six reflections written by UNM students, describing works by Florence Henri, Man Ray, and others. All artworks are from the UNM Art Museum’s permanent collection.

Florence Henri, Portrait; Plate 5 from 12 Fotografien, 1928.

Written by Bee Woods

Florence Henri is known for her mirror portraits and surrealist art style that is evident in her body of work. But this portrait of Margarete Schall feels like a proper look into the intimate relationship between Henri and Schall. The portrait speaks of the concealed queer connection between the two of them. Looking at the portrait through a queer lens, it almost feels obvious; the use of the mirror, never showing the subject’s truth, Schall looking away from the viewer, concealing the love and affection she held for Henri, keeping it between the two of them. It was theirs to have, but not to share with the wider public. To the queer eye, this photograph feels as intimate as a boudoir photo. You just have to look a little closer.

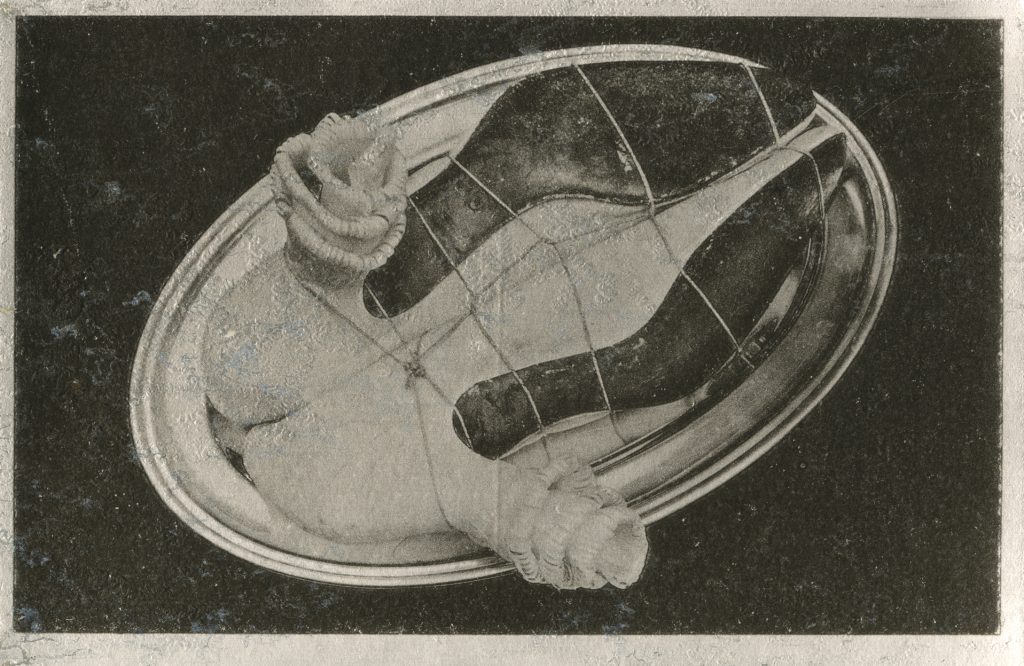

Méret Oppenheim, Published by Georges Hugnet, La Carte Surrealiste Premier Serie, 1937.

Written by Victoria Miera

One of the surrealist’s roles was to challenge contemporary social conventions, pushing back against the elitism present in traditional pictorialist ideas. Méret Oppenheim established herself by highlighting the absurdity of consumerism and the everyday object. In the work, My Nurse, she places a pair of white high-heeled shoes wrapped in twine on a dinner plate, resembling a roast fowl. This renders the object both unusable and inedible. What is an everyday object if not the mother, the wife, and the nurse, crucial to the recent world war, its recovery, and the upcoming repetition of destruction? Oppenheim comments on fashion as impractical via reflections on the modern world’s aestheticization of womanhood and consumerism.

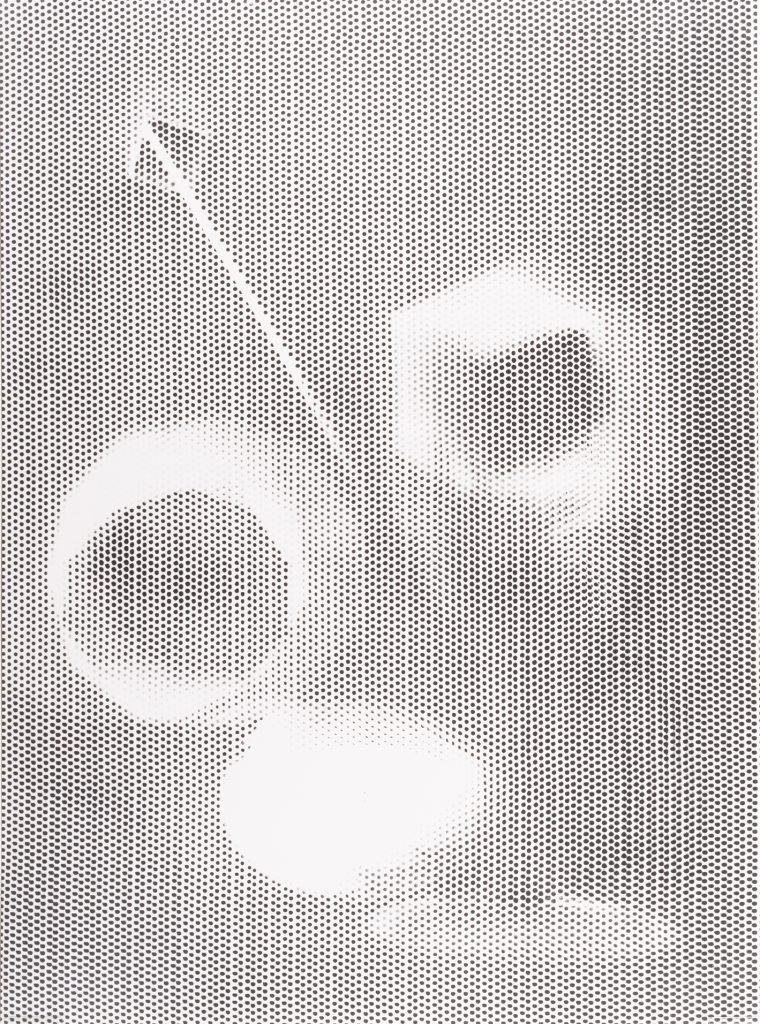

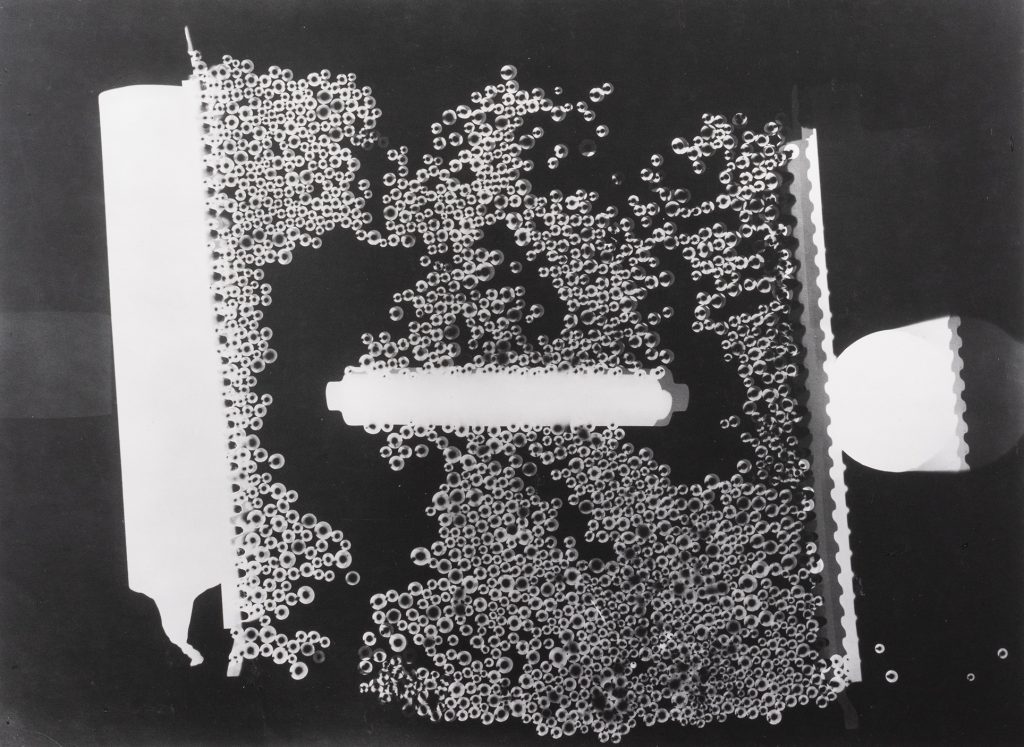

Man Ray, Photogram #1, #2, and #3 from the portfolio Man Ray: 12 Rayographs 1921-1928, 1922, printed 1963.

Written by Cintamani Schwab

Emmanuel Radnitzky, better known as Man Ray, was actively involved in the Futurist, Cubist, Surrealist and Dada movements. Man Ray photographed a world between reality and fantasy, and his “rayographs” captured his fascination with this distortion. Man Ray made these photographs by placing objects on photosensitized paper and then exposing them to light, leaving behind silhouettes of objects that often had dreamy, otherworldly, and indescribable effects. In Man Ray’s untitled works there is a strong sense of disconnect and nostalgia. His untitled works give no real indication of what is in the image but we are left with an imprint of a memory or a fleeting thought that is neither life nor art, but also is completely life and art.

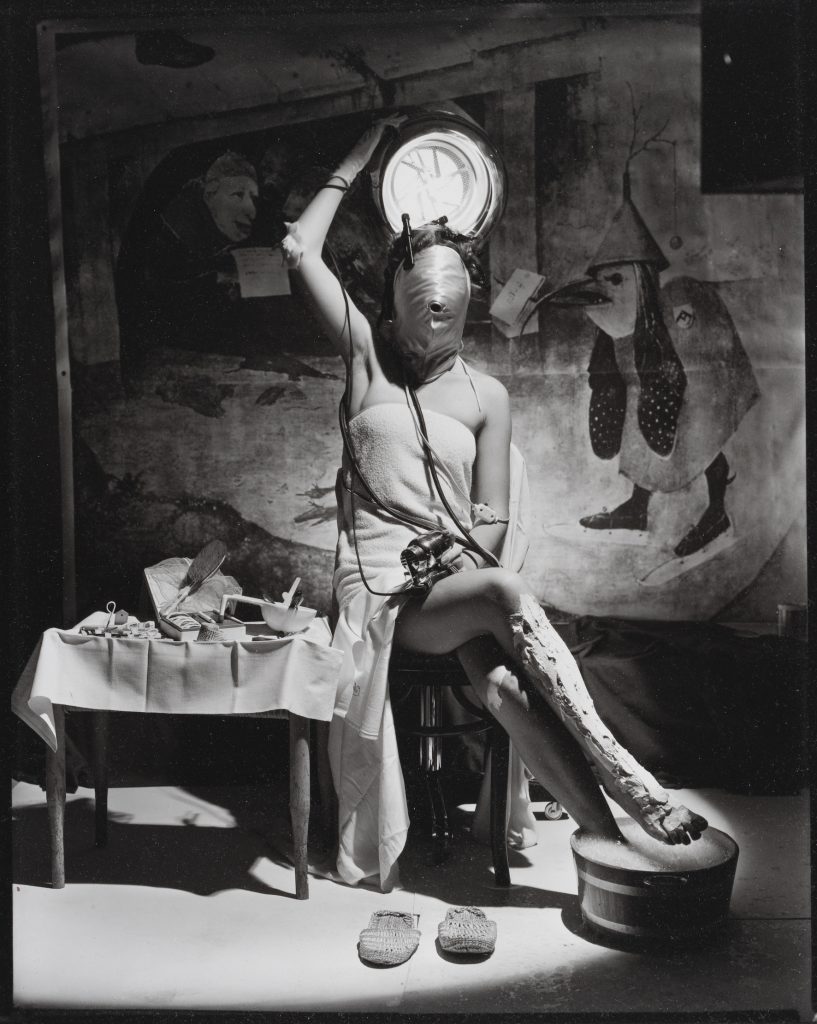

Horst P. Horst, Electric Beauty, 1938.

Written by Mahli Toscano

This iconic photograph embodies the era’s fusion of elegance and modernity, where timeless glamor meets the electrifying spirit of progress. A confident woman sits in the center of the image. She is bathed in a radiant, soft light that accentuates her features and poise. The woman wears a sleek gown, and her posture exudes an element of artistry and sophistication. Behind her, there is a backdrop of bold and surreal imagery. The interplay of light and shadow on the woman’s figure and the contrast of the dark background creates a visually captivating and almost dreamlike atmosphere.

Horst’s use of light and composition showcases a confident, avant-garde vision of feminine beauty against a backdrop of traditional art. This photograph serves as a visual commentary on the interplay between tradition and progress, as it celebrates the classical ideals of femininity while embracing the modern world’s dynamic energy.

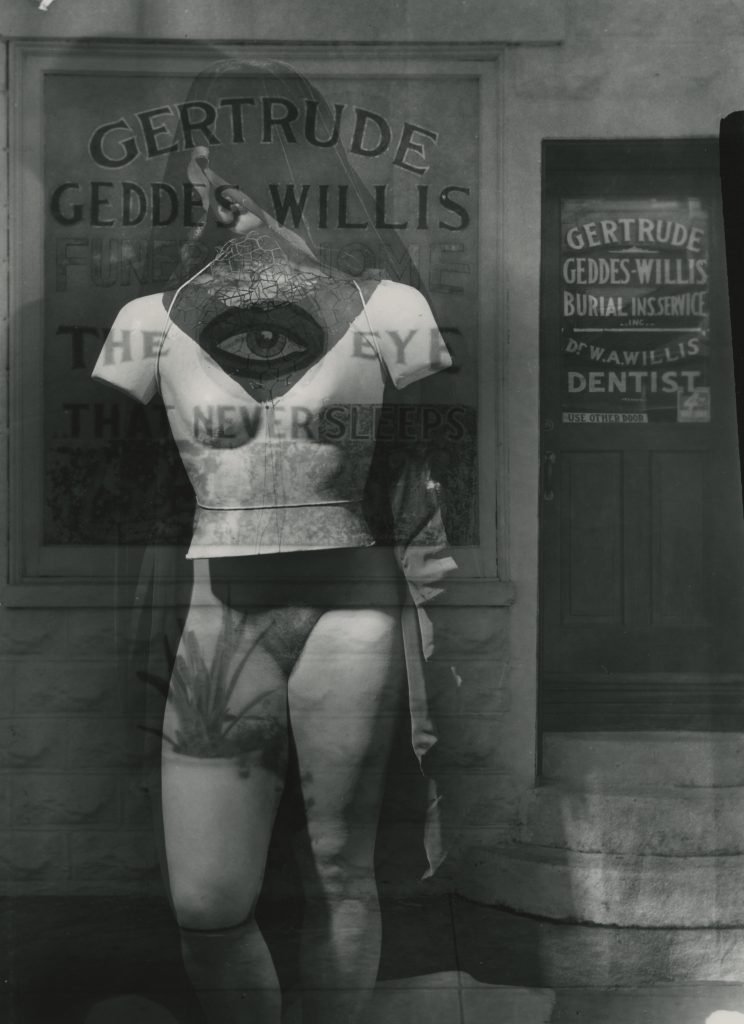

Clarence John Laughlin, The Eye that Never Sleeps, 1946.

Written by Rebecca Shalliker

Clarence John Laughlin produced dreamlike photographic compositions as well as a body of architectural photography. Working primarily in his home state of Louisiana, his images take on a distinctly southern gothic aesthetic. This aesthetic helped to present an essence of experience beyond a purely representational image. Through the use of various surrealist techniques, such as the double exposure used in this image, Laughlin’s photography dips into a dream state, an intentional quality on account of his self-proclaimed metaphysical interests. The Eye That Never Sleeps capturesboth Laughlin’s interest in architecture, with its background of a funeral business, and exposes his surrealist interests with the use of doubling that warps the images into a world beyond our own. Balanced both in our world and the deeper world of perception and imagination, Laughlin pushed the bounds of surrealism, allowing the everyday person to walk in the dream-like bayou of Laughlin’s own south.

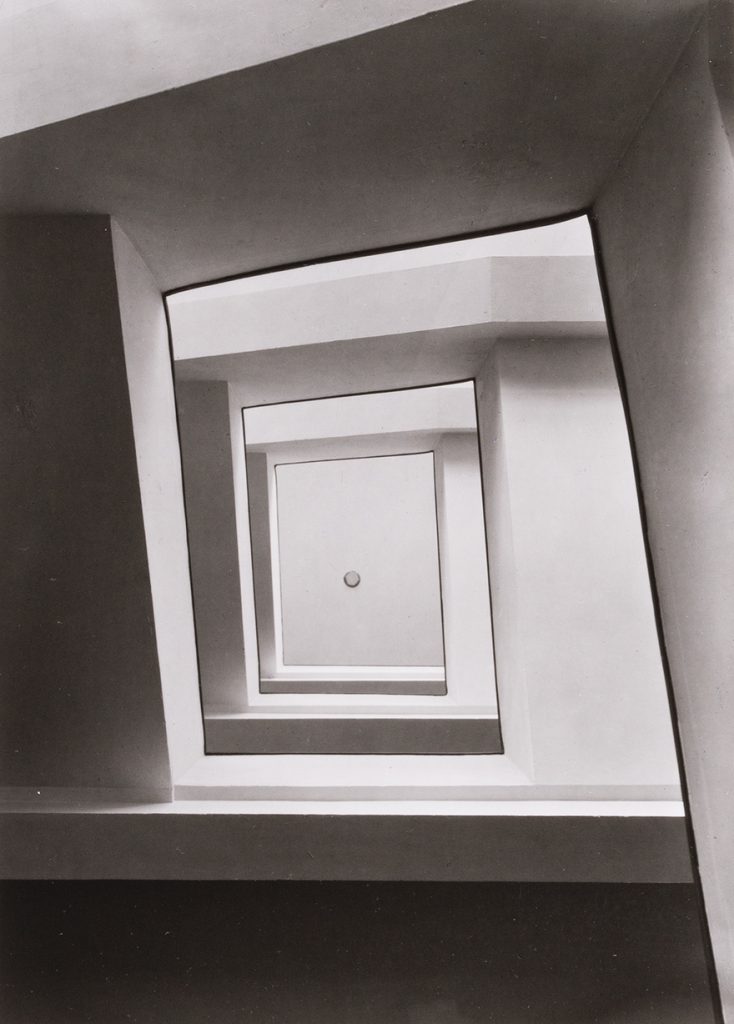

Werner Mantz, Treppenhaus Ursuliner Lyzeum from the portfolio 10 Photographien 1927-1935, 1928, printed 1977.

Written by Malachi Sanchez

Werner Mantz has chosen to offset the angle of this photograph as to not be flat or straight as we do not have anything to orientate ourselves with the space. He is keen to off center our only point of reference, the light. Mantz’s ability to play with leading lines and the golden ratio is evident here and throughout a lot of the works that he is known for. The photo creates an optical illusion building curiosity and allows for abstraction and a sense of depth.