Luis Jiménez: In the UNMAM Collection

Written by Hannah Cerne, UNMAM Research Assistant

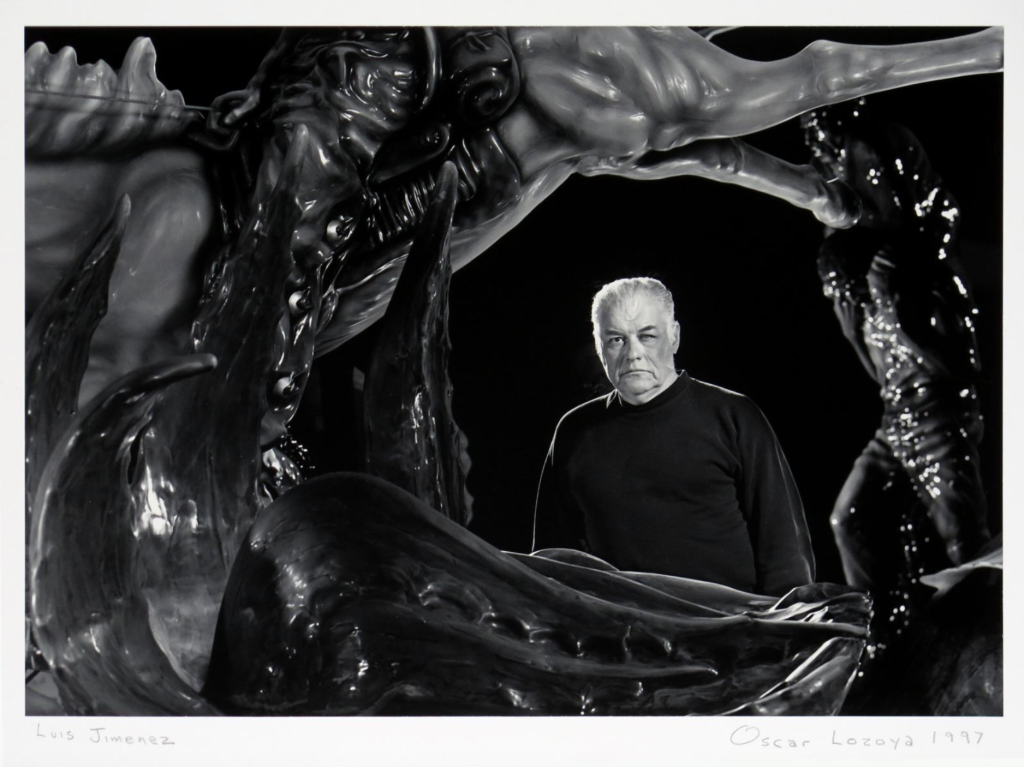

Figure 1. Photograph of Luis Jiménez, by Oscar Lozoya, in 1997 standing surrounded by his sculptures. Albuquerque Museum – One Albuquerque.

Luis Jiménez was an artist who constantly invented new ideas, experimented with unusual materials, and created new works while pushing social and political boundaries. His use of color and vibrancy on large scales set him apart from many other artists and sculptors. Jiménez’s engagements with Chicano culture through bold fiberglass sculptures shares a complex relationship with his own heritage and culture. (Fig. 1). Jiménez has been a well-known artist in New Mexico since his Roswell Artist-in-Residence Program, and settlement, in 1972-73.

Jiménez grew up in El Paso, Texas. His grandfather was a glassblower in Mexico and his father, Luis Alfonso Jiménez, who hoped to be a professional artist, ran a sign shop. Jiménez began working in his father’s sign shop at age six, here he was introduced to industrial materials such as fiberglass. Jiménez attended the University of Texas at Austin in 1960 where he graduated with a fine arts degree in 1964. He spent the next two years studying art in Mexico City before moving to New York City in 1966. While staying in New York, Jiménez found work as an assistant to sculptor Seymour Lipton, an American abstract expressionist sculptor, and as an arts program coordinator for the city of New York.

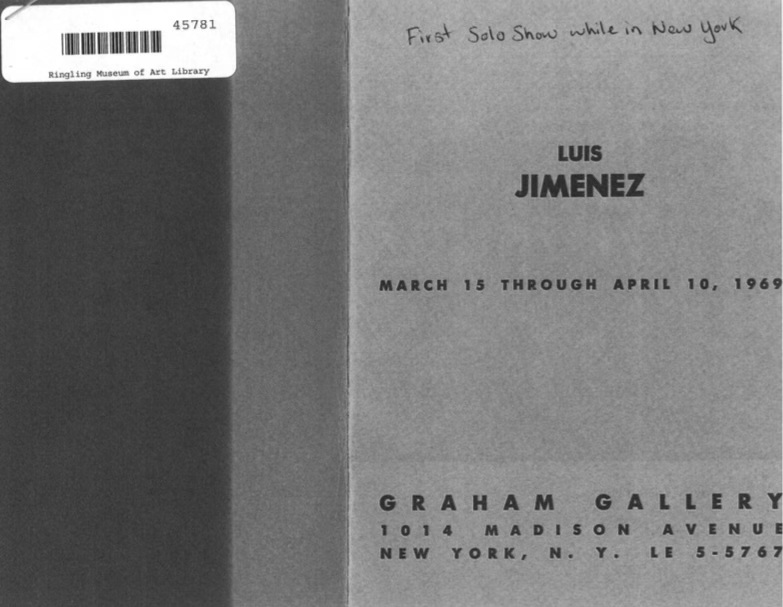

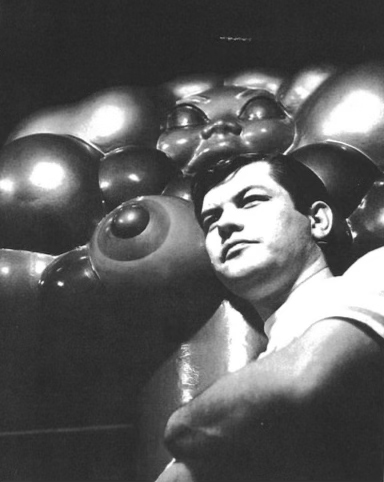

Figure 2. Scanned copy of the catalogue cover from Luis Jiménez’s first solo exhibition at the Graham Gallery in New York, N.Y. Figure 3. Photograph of Luis Jiménez in front of one of his sculptures at the Graham Gallery in New York, N.Y. from the exhibition’s catalogue.

By 1969 Jiménez found his chance to introduce his own work to the public. His first solo show was at the Graham Gallery in New York, NY. (Fig. 2 and 3). Jiménez’s works were received well by the public and immediately found a market of art buyers interested in his work. Jiménez showed a second solo show at the same gallery the following year. The success of his shows at the Graham Gallery allowed Jiménez to quit his job and become a full-time artist. By the early 1970’s his studio was becoming too small as his art career prospered, he moved back to El Paso, TX.

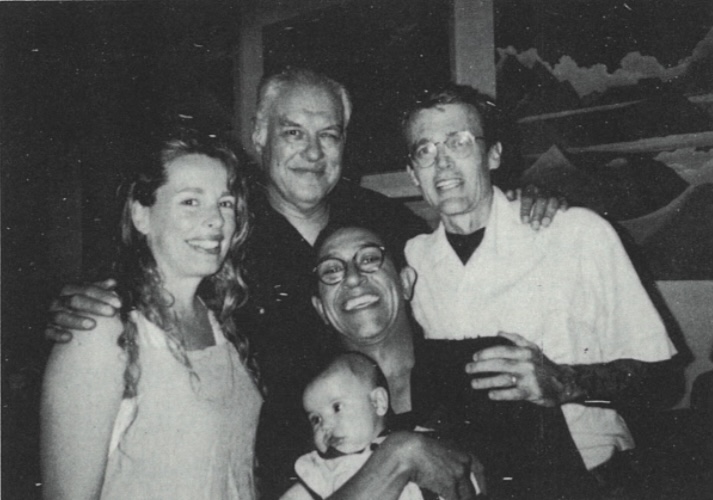

By 1972 Jiménez packed up his truck and moved to Roswell, NM to pursue his art. He was supported by Donald Anderson, a collector of his works. Anderson was the founder of the Roswell Artist-in-Residence Program which provided artists with housing, studio space, and income for a year. The program supported artists and allowed their careers to prosper. (Fig. 4). Jiménez quickly found an old, abandoned adobe schoolhouse built during the Great Depression in Hondo, NM. He turned the schoolhouse into his studio and home. After moving back to the Southwest his work increasingly focused on Western ideologies and stories. Many of his works during this period were seen as controversial, as public sculpture is often deemed.

Figure 4. Luis Jiménez pictured with former Roswell artists-in-residence and the Director of the Artist-in-Residence Program in 1997. (LEFT – RIGHT): Former artists-in-residence Diane Marsh (1980-81), Luis Jimenez (1972-73); Eddie Dominguez (1986-87) with son Anton, and Stephen Fleming (1986-87; 1991-92) Director of the Artist-in-Residence Program. Roswell Museum and Art Center Quarterly Bulletin Vol. 45, No. 4, Fall 1997.

One example of controversy over his work is with his sculpture Vaquero, modeled in 1980 and cast in 1990. Vaquero depicts a colorful and energetic Mexican cowboy riding a horse while waving a pistol in the air with one of his hands. The sculpture expresses Jiménez’s amendment to the traditional cowboy which is often depicted as American or of English descent. Jiménez discussed the development of cowboys, and the Mexican roots of Western activities in many of his sculptures. Vaquero was installed in Moody Park in Houston, TX, which is a largely Latino neighborhood, however the sculpture ignited criticism. Some members of the public perceived Jiménez’s sculpture as a poor representation of Mexican community and people. Despite Jiménez’s goal to represent his Mexican and Spanish roots and to correct history. With the community support in Houston to keep Vaqueros in Moody Park, the sculpture remains there today.

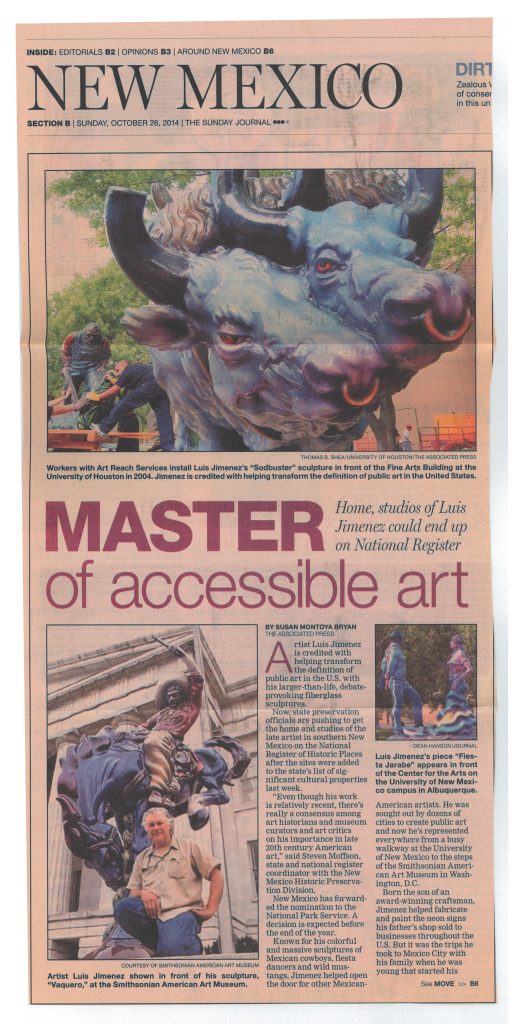

Jiménez continued to create controversial sculptures despite the lack of public approval. In 1992, Jiménez was commissioned by the Denver International Airport to create the sculpture titled, Mustang. The sculpture depicts a bright blue horse on its hind legs with bright red glowing eyes. Jiménez tragically died in his studio on June 13, 2006, when the hoist holding Mustang slipped and fell. Thanks to the New Mexico Historic Preservation Division, Luis Jiménez’s studio and home have been listed in the State Register of Cultural Properties and is under consideration in the National Register of Historic Places. (Fig. 5). Luis Jiménez’s memory and impact will continue to live on through his studio, home, and public sculptures.

Figure 5. Albuquerque Journal article written by Susan Montoya Bryan discussing Luis Jiménez’s home and studio being listed as a State Register of Cultural Properties. October 26, 2014.

Figure 6. Photograph of Luis Jiménez’s Fiesta Jarabe (1992 – 1996), Fiberglass sculpture, in front of the Center for the Arts at the University of New Mexico. Public Art at UNM – University of New Mexico Libraries (2023).

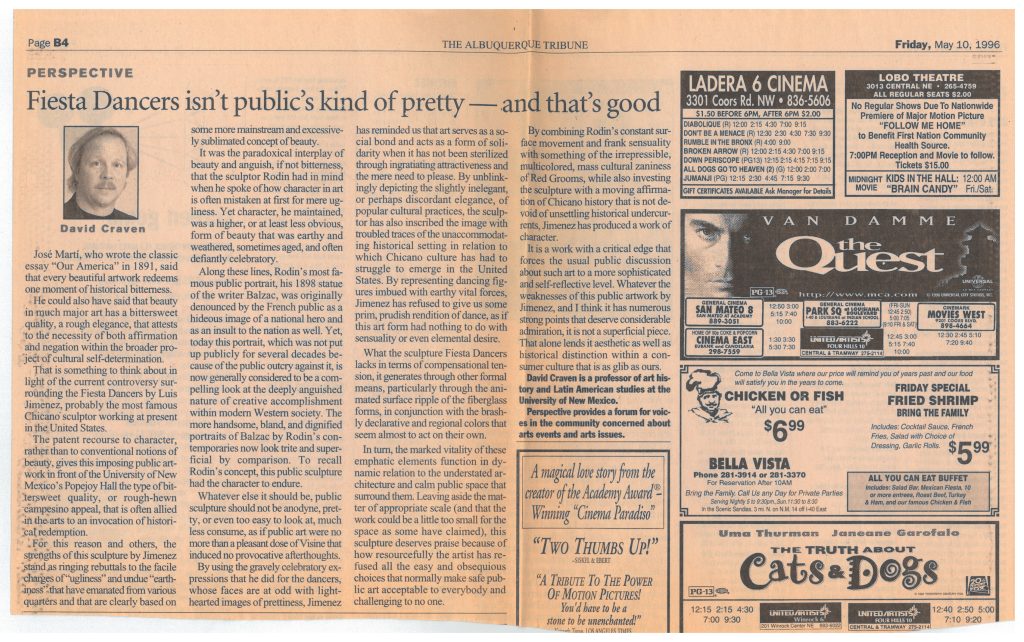

The University of New Mexico (UNM) celebrates Jiménez and his work by displaying one of his sculptures on campus as part of the university’s Public Art Collection. Located on the East side of the Center for the Arts is Fiesta Jarabe (1992 – 1996), installed in 1996. (Fig. 6). Fiesta Jarabe is constructed of fiberglass, epoxy, and metallic powdered paint. The sculpture presents male and female dance partners decorated in vibrant colors and posed energetically. The sculpture expresses Jiménez’s tribute to Southwest working-class people. When Fiesta Jarabe was installed, the sculpture was met with great delight as well as disapproval from the public. David Craven, a departed Art History Professor at the University of New Mexico, wrote an article published by The Albuquerque Tribune, now known as the Albuquerque Journal, discussing Fiesta Jarabe and the public’s reaction to it. Craven writes “…the strengths of this sculpture by Jiménez stand as ringing rebuttals to the facile charges of ‘ugliness’ and undue ‘earthiness’ that have emanated from various quarters and that are clearly based on some more mainstream and excessively sublimated concept of beauty.” As Craven states common opinions amongst the public discuss Fiesta Jarabe as “ugly” or “inelegant” he continues to explain the challenging work of art as representational, thought provoking, and historical. (Fig. 7).

Figure 7. Albuquerque Tribune article written by David Craven, a professor at the University of New Mexico, discussing Fiesta Jarabe and the approvals and disapprovals from the public. May 10, 1996.

The University of New Mexico Art Museum (UNMAM) holds a total of five works of art by Luis Jiménez in its collection. Currently on view are two works by Jiménez in For Every History Told: Chicano and Latinx Art and Representation a section of the exhibition Hindsight/Insight 3.0. The works include Rodeo Queen (1972) (Fig. 8) and Nat Love * Negro – Cowboy (1974) (Fig. 9). The Jiménez works on display in the main gallery at the UNM Art Museum were selected by Hindsight Insight 3.0 collaborator, and UNM Art History Professor, Ray Hernández-Durán along with UNMAM Curator of Collections and Study Room Initiatives, Angel Jiang.

Figure 8. Photograph of Luis Jiménez’s Rodeo Queen (1972), Fiberglass sculpture. The University of New Mexico Art Museum Collection (2023). Figure 9. Photograph of Luis Jiménez’s Nat Love * Negro – Cowboy (1974), colored pencil on Strathmore paper. The University of New Mexico Art Museum Collections (2023).

I spoke with Jiang about the inclusion of Jiménez’s pieces in Hindsight Insight 3.0. Jiang shared her insight saying,

“It was important to feature Jiménez, one of the most celebrated Chicano artists from the Southwest, in a show about Chicano and Latinx art. We’re very fortunate to have the pieces we do. Rodeo Queen and Nat Love are both vibrant representations of the type of figure Jiménez was interested in making visible. One is an archetype (the Rodeo Queen) and another is a real historical figure (a Black nineteenth-century cowboy). Jiménez believed both were essential to the construction of the West, both literally and as figures that shape our perception of it.”

Jiang’s significant knowledge of the UNMAM collection is crucial as the Art Museum continues to display innovative exhibitions and experiences.

Luis Jiménez lived an inspiring and audacious life as a man and artist. His willingness to be bold and experiment with new techniques and colors showed his fearlessness as a creator. His captivating works of art have truly been a considerable contribution to the Public Art Collection at UNM and the UNMAM collection. See Jiménez’s Rodeo Queen (1972) and Nat Love * Negro – Cowboy (1974) in Hindsight Insight 3.0 at the University of New Mexico Art Museum now through December 9th, 2023.