Sagrado Corazon Sacred Heart: An Interview with Delilah Montoya

Written by Hannah Cerne, UNMAM Research Assistant. Editor’s Note: This transcript has been edited for length and clarity.

Portrait of Delilah Montoya photographed and published by the University of Houston in an interview by Nerissa Gomez on August 5, 2020. https://uh.edu/kgmca/about/news/2020/delilah-montoya.php

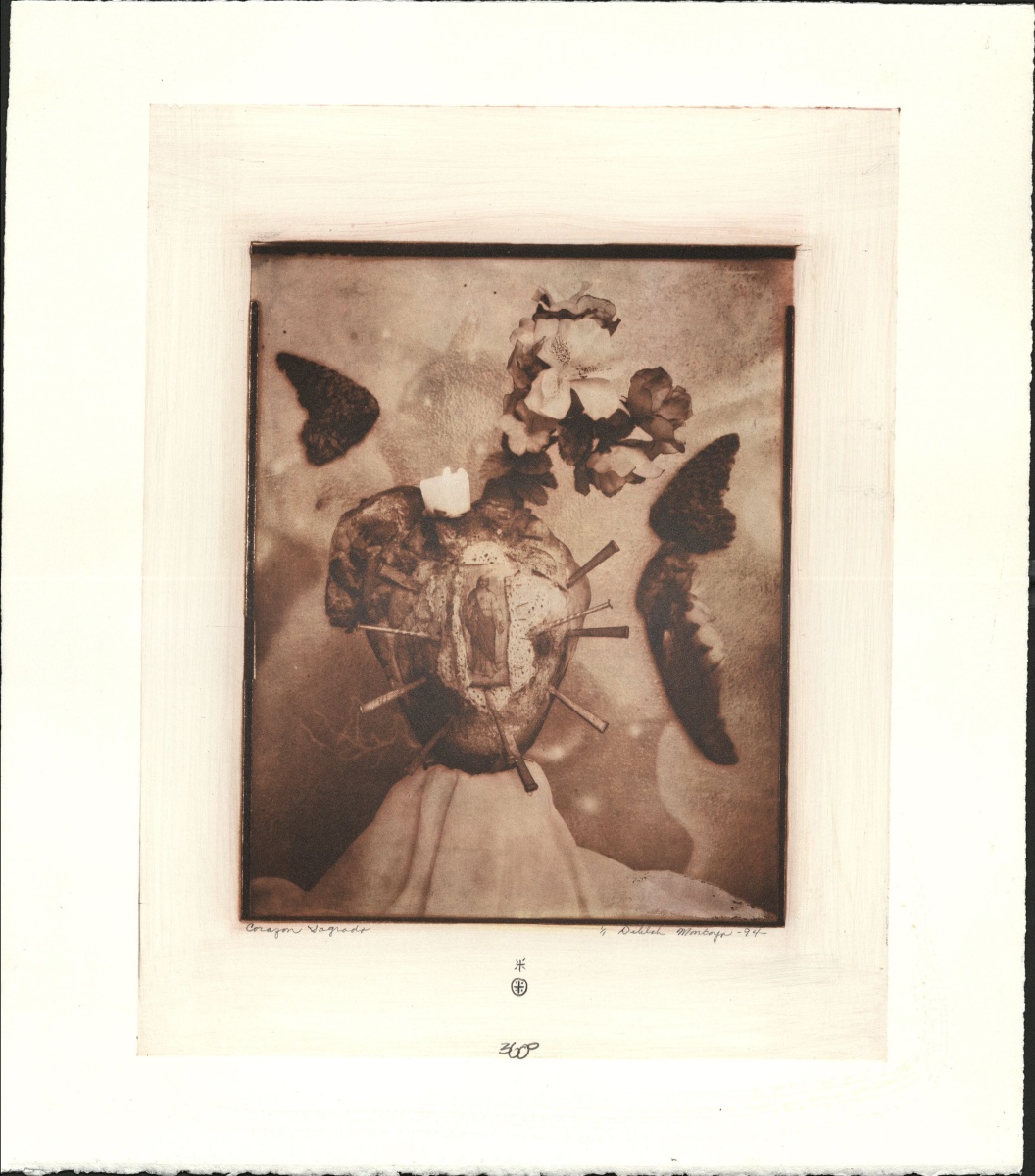

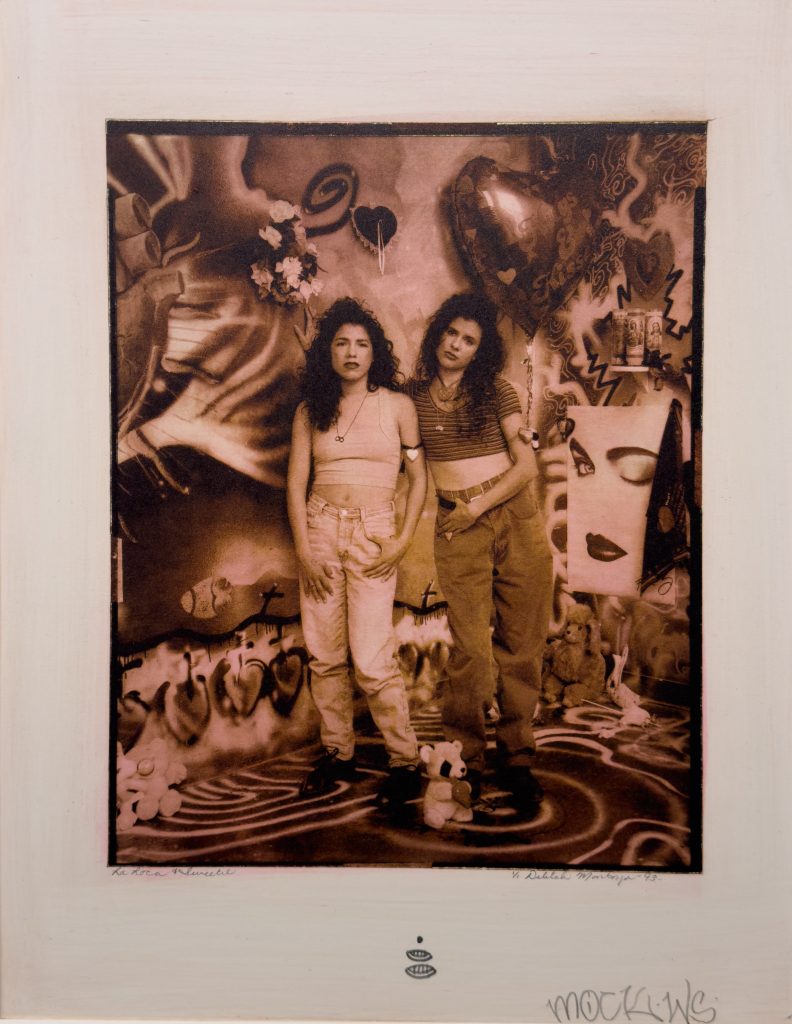

Delilah Montoya is a contemporary Chicana artist who was born in Fort Worth, Texas and raised in Omaha, Nebraska. Montoya moved to New Mexico to earn a BA, MA, and MFA in Photography from The University of New Mexico (UNM) between 1984 – 1994. Recently, I had the opportunity to sit down and chat with Montoya over a Zoom meeting. Throughout our conversation, she spoke of her experience as a student at UNM, her relationship with the University of New Mexico Art Museum (UNMAM), and her research and artwork as she pursued her education. Montoya was one of the graduates in 1994 selected to be part of the Juried Graduate Student Art Exhibition at UNMAM. The exhibition featured her works titled Corazon Sogrado (1993), El Misterio (1993), and El Misterio de Triste – Sueltame (1993). A collotype from Montoya’s master’s thesis titled, Sagrado Corazon: Loca y Sweetie (1993), is currently on display in the exhibition Hindsight Insight 4.0 at UNMAM throughout the Spring 2024 semester.

Read the full transcript of my conversation with Delilah Montoya below.

HANNAH CERNE: Hi, Delilah! How are you doing?

DELILAH MONTOYA: Hi, I am doing good. Thank you.

HANNAH CERNE: So, my first question is, what drew you to attend UNM for your undergraduate and graduate degrees?

DELILAH MONTOYA: Well, there were a couple of things. My other family is from New Mexico, and we used to visit when I was a kid living in Omaha, we would always come back to New Mexico to visit relatives, and it was just so much better here. I lived in Omaha, Nebraska where there was a meat packing place. We lived a half mile from stockyards, and it smelled bad. After a while, you didn’t smell it anymore, but I remember when we’d come back home from Las Vegas, New Mexico, with my mom, and there were mountains, blue skies, fresh air, and all those things. Then we started heading back to Omaha, and we’d get to the outskirts, and it smelt bad there. So, there was always this feeling that things were nice and beautiful there.

I attended a two-year college, Metro Technical Community College, and I started taking photography. I was told that there were people in Albuquerque, New Mexico at UNM, and that there was a high-powered photography program there. People like Van Deren Coke and Beaumont Newhall were at UNM, and these are people being studied now. I realized that I wanted to have the opportunity to study with some high-powered people, and I wanted to come back to New Mexico too, it was a win-win situation.

I was going to be a Chicana artist, and there were a lot of people like my teachers in high school who said there’s no such thing as Chicana art. I thought “Oh, let me show you. I’m going to reinvent myself. I’m going to have my identity.”

HC: How did you develop the concept for your master’s thesis? Did your concept change or evolve throughout the process of working on it? Did anyone in your life family, friends, professors, or mentors inspire your work?

DM: So, I had one master’s that I did, and it was Saints and Sinners, and the other was Corazon Sagrado Sacred Heart. One of the reasons I wanted to come back to New Mexico was because I was interested in my mother’s culture, and I wanted to find out more about it and base my aesthetic on it. I wanted to get involved because I was very much involved in the Chicana movement in Omaha, NE. I was going to be a Chicana artist, and there were a lot of people like my teachers in high school who said there’s no such thing as Chicana art. I thought “Oh, let me show you. I’m going to reinvent myself. I’m going to have my identity.” The creation of an identity that was truer to my interests and family history.

My thesis Corazon Sagrado Sacred Heart began with my fascination with the Sacred Heart. The Sacred Heart is one of those things that, like in Catholicism, it’s a disembodied heart. I asked myself when did the disembodied heart show up in Catholicism? One thing that I found about the disembodied heart is that it showed up after the Latin American Conquest and New World Conquest. So, we know what the disembodied heart meant to indigenous people in Mexico, the disembodied heart was a part of the sacrifice. So, I thought, wait a minute, it shows up after the conquest, and that was of huge significance to me. Because we see Catholicism utilize the Sacred Heart to try and get a whole group of people to change their identity. They’re transforming an identity, and one of the ways of doing that is to bring in the icons that they understand. Now, what does the disembodied heart mean? So, I began to think about it and look at the disembodied heart and the way it is perceived. I thought about it and thought I would take portraits of the Chicano people in Albuquerque rebuilding their hearts and calling it the Sagrado Corazon Sacred Heart.

Delilah Montoya’s selected works for the Juried Graduate Student Art Exhibition hosted by the University of New Mexico Art Museum, El Misterio (1993), Corazon Sogrado (1993), and El Misterio de Triste – Sueltame (1993). Images collected from the Center for Southwest Research at the University of New Mexico, in the Corazōn Sagrado/Sacred Heart Collection.

The biggest critique I have of UNM is that they did not have people there who understood what I was going through at that time, in terms of diversity. Because they go out and seek professors from outside diverse communities here in New Mexico, and they do it repeatedly.

HC: I love hearing all the backstory behind that concept. What was it like working on your master’s thesis at UNM? Are there any peers or faculty who supported you in this process?

DM: Oh, it wasn’t easy, I remember, but what was helpful was that the equipment was there, and they gave me access to it. The biggest critique I have of UNM is that they did not have people there who understood what I was going through at that time, in terms of diversity. Because they go out and seek professors from outside diverse communities here in New Mexico, and they do it repeatedly. For instance, New Mexico is well known for the folk traditions of Santos’, they’re collected all over the world, but not one of those Santos artists has been invited as a faculty member at UNM. New Mexico has Native American fine jewelers, whose work is valuable and known all over the world, but UNM has no jewelry department. So, what happens is the UNM’s Art Department is doing missionary work. So, that’s always been a critique of mine, why are all the artisans from New Mexico, who have such a strong cultural connection to the land and communities pretty much left on their own? You know, UNM gets a lot of tax money from the population, so why is the public not benefiting from the educational process? I would say, if anything, that would be my one critique that they need to do a better job.

I would say UNM was excellent in providing the resources that I needed. They were excellent in providing academics that I needed to continue and seek out professorships. I would say that I would have liked to have seen them give us a little bit more about how the art world operated. I learned those things through my mentors like Louise Menis, Jesus Moronis, Yolanda Lopez, and Cecilia Serbia. They were well-situated with the art world, and I was able to ask them questions and just watch to see how they approached many situations. They answered questions such as, what do you do, how do you approach a gallery, what can you expect out of a gallery, how do you get that clientele, how do you work for yourself, how do you price your artwork, what do you do about taxes, and, how do you write up an artist statement or a grant proposal?

My peers and faculty who supported me through this process were Flora Clancy. Flora Clancy was awesome; she was one of the only people who showed up to support me at a museum show in Santa Fe, NM. Flora Clancy was a great person, and you know I have to say Patrick Nagatani was good, also Tom Barrow, and Betty Hahn. Betty Hahn probably gave me the best advice I have ever received, I told her I was working full time because I have a daughter and I was not able to be a teaching assistant and she just looked at me and said, “Once you graduate you will be able to take on a teaching position.” And you know what, she was right.

Delilah Montoya’s selected works, hung in her studio space, for the Juried Graduate Student Art Exhibition hosted by the University of New Mexico Art Museum in 1994. Image from the University of New Mexico Art Museum Archives.

I work off the idea of previous themes, for instance, it’s been said the Sacred Heart portraits show up in my latest body of work, which is contemporary Casta portraiture. It’s kind of like going back into the community, photographing the community, one can think about it as the next step.

HC: How has your work evolved since you graduated from UNM? Are there themes you explored during your graduate studies that you’ve since returned to?

DM: I don’t generally return to themes and the reason is because you work into it, and you have a certain mind and it’s hard to go back into that mindset again. It’s a conceptual process, so when I am there with it, I am right there with it and when I stop doing it, I’m not. I don’t have that kind of conceptual process going on anymore, so I don’t return to themes. I work off the idea of previous themes, for instance, it’s been said the Sacred Heart portraits show up in my latest body of work, which is contemporary Casta portraiture. It’s kind of like going back into the community, photographing the community, one can think about it as the next step. The evolution of the Chicano consciousness.

Casta 12 (2018) by Delilah Montoya from the Contemporary Casta Portraiture: Nuestra “Calidad” series. Image courtesy of PDNB Gallery. https://www.pdnbgallery.com/contemporary-casta-portraiture-nuestra-calidad

HC: After graduating from UNM, what was the transition like from being an art student to becoming an artist?

DM: I don’t know if I ever thought of myself as an art student. I always thought of myself as an artist. In saying that, it’s because I saw UNM, or any school I went to, as a studio space where I could go to get resources that I needed to evolve my work, to make the work. We are all artists. It’s not like suddenly, we’re going to wake up and realize, it’s something that you always do, it’s innate.

I began to think about how so much of the time with an objective thought creates a condition where there’s this assumption of a particular culture, and how in many ways this created a pan-identity. Now, how much of the Chola is a pan-identity?

HC: Yeah, I think that’s great. It kind of takes away the wall people build inside their heads by saying, “I’m not an artist until I get to this step…” or “…until I graduate…” With your mindset, you’re always an artist, and you don’t feel like there’s a barrier stopping you from being one. Your piece, Sagrado Corazon: Loca y Sweetie (1993), will be on display in the exhibition Hindsight Insight 4.0 at UNMAM, what are your thoughts surrounding this piece? What was the backstory? How does it feel for the artwork to be on display in this exhibition?

DM: Well, I feel very honored that they bought the piece into the collection, that’s an incredible thing. I never thought that would happen to tell you the truth. It was my graduate work, but that work did well, it’s gone into a great collection. I feel honored that they thought so highly of the work. The backstory of the piece well, I was thinking about the Chicana identity and what that looks and feels like. When I was a student in class we talked about the subjective and objective, I don’t know if they still talk about that but, the subjective was what it was like being in the environment itself and the objective is like the distance, more observational. In photography, there’s this whole idea of the subjective and objective, and certainly, during this period there were a lot of curators that were thinking of those things. I was thinking about it in terms of the way documentary photography was working and I remember a lot of documentary photographers would talk about how, because they had the objective position, they could not see what was happening, and I was pushing back on that. I thought, how is it you would understand all of that, that you would understand what is going on without really getting inside of it and looking at it? Or are you trying to tell me that, for example, an Indigenous person would not know their own culture, and how to interpret their situation? Are you trying to tell me there is no such thing as a lived reality?

I began to think about how so much of the time with an objective thought creates a condition where there’s this assumption of a particular culture, and how in many ways this created a pan-identity. Now, how much of the Chola is a pan-identity? So, I asked the two girls, “Hey do you think you can kind of give me that Chola look?” They were performing that identity, I knew it, and they knew it. Both were students at UNM, I asked them to be my sitters and they said, “Yeah.” Then I thought, I wonder if anybody would buy this. The LA County Museum was the first institution to purchase the work. So, when UNMAM told me they were putting it up in a show about identity, I thought well that’s perfect.

Sagrado Corazón: Loca y Sweetie (1993) by Delilah Montoya. Collotype, 2023.3.1, University of New Mexico Art Museum.

HC: What does work in photography mean to you? Why have you chosen to work in this medium? What drew you to portraiture?

DM: I used to do a lot of drawing and watercolor, but I did photography because I could earn a living, and earning a living was an important thing for me. The community drew me to portraiture; I was interested in portraying the Chicano community.

HC: Thank you so much for your time today. I truly appreciate it and thank you for all your amazing answers to the questions.

DM: Yeah! Take care!