Interview with Andrea Polli: Hindsight Insight 5.0

Written by Hannah Cerne, UNMAM Research Assistant and Study Room Assistant. Editor’s Note: This transcript has been edited for length and clarity.

Andrea Polli discusses her piece, Untitled, made of glass, ceramic and colorants during the UNMAM Birthday Bash on October, 5, 2024.

Andrea Polli, a collaborator of the Hindsight Insight 5.0 exhibition at the UNM Art Museum, is a Professor with appointments in the College of Fine Arts and School of Engineering at the University of New Mexico (UNM). She is Director of UNM STEAM and the Mesa Del Sol Endowed Chair in Digital Media at UNM. She is an artist who works with art, science, and technology to create public works of art, media installations, and community-focused works. Polli holds an MFA in Time Art from the Art Institute of Chicago and a PhD in Computing Communications and Electronics from the University of Plymouth in the UK.

HANNAH CERNE: How did you get interested in art/science/technology and sound art, was the interest always there?

ANDREA POLLI: Really good question, I think I realized I was interested in art and science in high school, and I knew I wanted to work in that field. I didn’t get involved in sound art until I was in graduate school at the Art Institute of Chicago. The reason I think I was interested in art and science is because I had done a lot of studying in art history during my undergraduate degree. During that time, I studied classic American abstract painters like Jackson Pollock. During my graduate degree I became interested in sound art because I thought it was abstract, I thought it was the most abstract kind of art. But now, I think I realize that it is not, it has sort of clear meanings and messages that are in musical structure and sound is certainly just another way of experiencing it.

I could say a lot more about that, I did a lot of study and research on sound, especially soundscapes because I was doing sonification of data, particularly atmospheric science-related data, and I would be doing sonification, taking that data and translating that into sound. But the model I was using for the resulting sound was the soundscape rather than music. I have spent a very long time and continue to study the soundscape.

Image of Promessom by Andrea Polli on display in Hindsight Insight 5.0. Photograph by Stefan Jennings Batista.

HANNAH CERNE: How has your journey in bio-art and science developed throughout your artistic practice?

ANDREA POLLI: Soundscapes can be man-made but natural soundscapes are amazing, informative, and filled with ecological information that humans may not be able to gather with their eyes. When you talk about the intersection between art and science there are a lot of other creatures that create sound, and vibration, and life in general is a sound-creating thing.

John Cage talked a lot about silence as never existing. He went into a sound isolation chamber and he heard very loudly his own body, his heartbeat, nervous system, so life is always creating vibration and sound. So, I think there is a natural connection there. But I think there was also a connection of working with the atmospheric science data, which I started with back in 2000, maybe a bit before. I collaborated with meteorologists, and at that time I was interested in just the beauty, power, and sublime nature of storms and other types of weather activity I had not connected to global warming. I knew that it existed, but it wasn’t until 2004 that I started working with some climate scientists and got the message of what was happening with climate change and its significant impact on life, ecology, and our planet. This is an element of my development, it’s kind of interesting because I came to it through computation, rather than working in the field. Although soundscape recording brought me into the field, I was engaged with computational sonification and visualization before that as an artist.

I was humbled by working with living organisms … It was an eye-opening experience and keeps bio-art fascinating to me because there are so many variables, and maybe you can’t even reduce it to the variables…

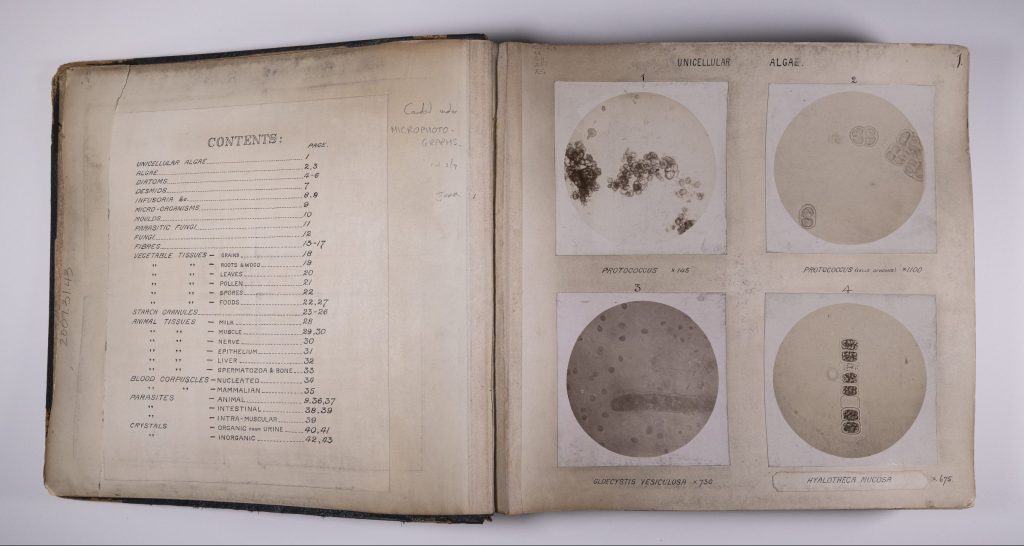

HC: As a collaborator of Hindsight Insight 5.0, you were asked to view the nineteenth-century album of microscopic photographs of the natural world. What was your initial impression of the object from the UNM Art Museum’s permanent collection?

AP: Well, these images at the time they were taken were so new and amazing. These were things people had not seen before, so it was a technology that extended the vision of invisible things and allowed people to see shapes, forms, and movements that were never seen before. I think in many ways my work has always been about that, or at least since 2009 when I started working on the Particle Falls project, which is about invisible things, or maybe perceiving invisible things, even the sonification work.

Particle Falls, 2010, installed in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, projected onto the Stevens Center building in 2018. Photograph from North Carolina Clean Energy Technology Center via Clean Air California.

In that way connecting to the book was easy for me. I think the aspect of people maybe not understanding what they are seeing when looking at my work was a part of microscopic imagery. Still, to this day, there is so much development in imaging for science, all the way down to nanotechnology. We are seeing things in the nanotechnology world that are a reconstruction, and we do not understand what we are seeing. Which is fascinating and wonderful. It is a fantastic space to be in.

I started to grow a lot of different organisms, and you see that in the exhibition, Fiona Bell’s amazing work and Kaitlin Bryson’s amazing work. I have done a lot of that, and I am sure I will continue. When I started to do it, I had a perspective on it that was computationally informed. I thought, well I do hard things, I program computers, that’s hard and it takes a lot of knowledge and background so I felt like I could jump in confidently into growing organisms. If I follow instructions and conduct research into what is happening, I can do this, right? I was humbled by working with living organisms, because in my opinion and experience, sometimes things just die and there is nothing you can do about it. I think this is something that is a humbling experience for all of us as living beings and in the world. It was an eye-opening experience and keeps bio-art fascinating to me because there are so many variables, and maybe you can’t even reduce it to the variables, there may be other things going on that we do not know about, and this makes it so fascinating.

Unidentified photographer, Microphotographs Presented to the Royal Institute of Chemistry by Henry Droop Richmond, c. 1877-1883. Bound volume with 43 pages of albumen print photographs. Transferred from the University of New Mexico Fine Arts and Design Library.

HC: How did you use the nineteenth-century album of microscopic photographs as an inspiration for your artworks displayed in Hindsight Insight 5.0?

AP: I am trying to create new forms; I am trying to create forms of things that have never been seen before and I think there is some similarity with the book in that way. The forms are often organic, some pages in the book show geometric forms which blows my mind seeing geometric combined with organic. This was a structure I played around with. Also, the idea of growing things, there is a great book, Understanding Living Systems, that just came this year. The book talks about comparing crystal growth to biological growth. Something that I have been working with is a kind of growing of this glass powder. I developed the system in a kiln for glass to become porous and transform its shape dramatically through a firing process. I was interested in porosity, but also growth. The porosity is significant in terms of this project, so it turns out the material that worked the best for me in trying to get the glass to foam, grow, and become porous was calcium carbonate. Calcium carbonate is also one of the most prevalent biominerals in the earth and it’s what makes up our bones and shells. I am curious about porosity because our bones are porous, right? The cells and organisms in the book are porous, there is an exchange that is happening within bodies and between bodies and that is caused by porosity. I am fascinated with the materiality of that.

There is kind of this chicken and egg thing going on for me in this exhibition. In that, there were things I was working on and interested in. I started to dig deep into the research and learned, for example, that the Earth has an incredibly diverse different amount of minerals, compared to other planets. It has been determined that the diversity comes from living micro-organisms under the earth. So, a lot of what I have been working with is these different minerals that do all kinds of different things. For example, the color seen in some of those pieces is also caused by minerals reacting at high temperatures. We benefit from the existence of diverse materials because of micro-organisms.

Andrea Polli prepares the piece, Untitled, made from rubber 3D prints. Image courtesy of Mary Statzer.

Untitled by Andrea Polli on view in Hindsight Insight 5.0. Photograph by Stefan Jennings Batista.

HC: What do you hope people take away from your artwork and the Hindsight/ Insight 5.0 collaboration?

AP: I hope that there is a greater awareness of the microscopic world. Not too long ago our world was getting out of COVID. The idea of micro-organisms being frightening, and certainly they can be terrifying organisms, but I think their presence, variety, diversity, and possibility of being can be beneficial. The materials that Kaitlin Bryson and Fiona Bell are creating are potentially materials that will be so much more beneficial if there is widespread adoption of them.

HC: What does the intersection of art and science mean to you?

AP: That is interesting. I think bio-art, well, I am going to say this definition and it will make my work, not bio-art, and that is okay. I think bio-art needs to have been created somehow with living organisms, and I think it needs to have evidence of organisms as a part of it. I think there is bio-informed art, bio-inspired art, or eco-art, but I probably should not be that strict. I think some things are called bio-art that do not necessarily use living things, I use, for example, an unusual approach to a bio device and how it interacts with living things, so that is the bio part. But what makes it art? Well, I guess that is the million-dollar question, isn’t it? It’s an expression, but it also might be a commentary, a critique, or a reaction. So again, you go back to that statement of “what is art?” But, good art, we will go in that direction, is work that makes you think and gives new insights into biology and life.

Andrea Polli, Fiona Bell, Spectrospira, 2024. Photograph by Stefan Jennings Batista.

HC: What did you learn from the Hindsight Insight 5.0 collaboration with UNM staff and faculty?

AP: Oh, so much! I will be using Fiona Bell’s recipe book; I have even started saving my eggshells to try out one of her recipes that calls for eggshells. Sharing materials with the artists and collaborating with Fiona Bell on the Spectrospira piece was great! Also, the greater deep dive into biominerals has been important for me because starting that work has been about minerals and landscape, but also looking at their relationship to living things historically has become a great direction of research for me. I have learned so much from Mary Statzer. Her process is so methodical, as artists we got to see that part of that process, and that was fascinating. We got to see what was in the permanent collection as she pulled it out and made decisions was incredible, seeing the whole refining process was amazing. I learned how some of my pieces at my studio functioned in a gallery space and with audiences. Seeing it all is hard to put in words, but it is something that I already feel is important with my work moving forward.