The Opening of Hindsight Insight 5.0

A Retrospective Analysis to Accompany the Exhibition’s Final Week

Written by Ava Marr — an undergraduate student studying Art History at the University of New Mexico with interests in modernity and the intermixture of science, technology, and art.

Museum visitors interact with SCOBY Breastplate by Fiona Bell. Photograph by Aziza Murray.

On the fourth Friday of August 2024, the University of New Mexico Art Museum opened its first exhibition of the 2024-25 academic year. The evening focused on two separate openings for the fifth and final installment of the Hindsight Insight series, Hindsight Insight 5.0 — a collaborative exhibition in the Main Gallery consisting of works in the field of bio-art and an emotionally moving exhibition in the Coke Gallery, Notes on Care, by UNM Photography MFA alum Rachel Cox. The gallery spaces contained pieces related to the intersection of biological and artistic practices, with an assortment of interactive pieces that allowed for an inclusive museum experience. In addition to these installments, the evening featured a pop-up event organized by Basement Films that paid homage to the projectionist Elias Romero known for his advancements with overhead projectors beginning in the late 1950s. To connect the themes of these separate shows, one can look to Henry Droop Richmond’s bound volume of nineteenth-century photographs from the museum’s permanent collection entitled Microphotographs Presented to the Royal Institute of Chemistry, which contains upwards of 40 pages of images that could be argued as predecessors of bio-art.

The event began at 4:00p with opening remarks planned for 4:45p. I wanted to arrive with enough time to grab a lovely assortment of Mediterranean-Latin fusion crafted by Fresko, an Albuquerque-based food truck. Sampling my plate of smoked brisket chimichangas and house made hummus with veggies, I surveyed the scene of various faculty and students from differing departments gathering in the Center for the Arts, with us all enjoying our plates and engaging in conversations with one another. This period allowed anticipation to build for what might be beyond the entrance of the gallery.

Once I had finished my refreshments and cleansed my palette with a glass of iced cucumber water, I made my way into the Main Gallery. Just beyond the welcome counter and down a light set of stairs one would see Hindsight Insight 5.0. Your eyes could dart all over the room from the many seemingly biological, perhaps living, art works. Many colors, mediums, and techniques filled the space and encouraged your legs to guide you to the first work that caught your eye.

Untitled by Andrea Polli. Photograph by Stefan Jennings Batista.

What first caught my eye was Untitled, a piece comprised of glass combined with colorants that bubbled on the surface like a breathing mass. I felt as though I could almost see a set of eyes matching my gaze back through the glass, as though someone or something was looking at me. This 3-dimensional work was shaped by Dr. Andrea Polli, who I later had the pleasure of conversing with. From Untitled, I continued to stroll through the gallery, sticking close to the walls so I could read the object labels with ease. I felt myself being drawn to analyze everything in sight as the placement of experimental textiles, sustainably 3-D printed vessels, a glass-blown receptacle containing spirulina algae, conceptual light installations and more was as exciting as it was unknown to me. I was intrigued by the local eruption of bio-art and the future scholarship that has yet to be authored.

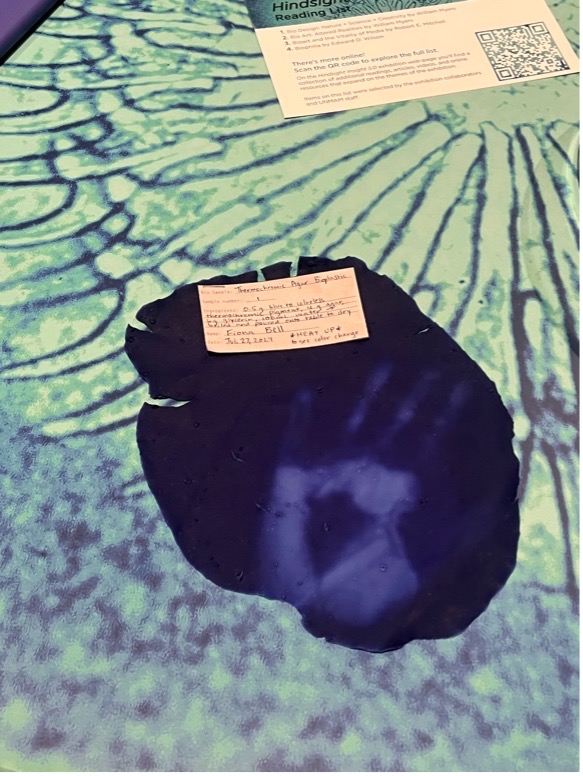

At one point in the evening, prior to opening remarks, I found myself seated at one of four vibrant tables based off photographs from the microscopic album. Within the swirling blue center of one of these tables sat one example of the previously mentioned interactive elements in the exhibition: a basket that contained an array of bioplastic and SCOBY textile swatches. These swatches corresponded with similar works created by Dr. Fiona Bell, Kaitlin Bryson, and UNM students that were pinned onto a moveable wall. This allowed the audience of the gallery to have a physical and sensorial experience from the work that likely matched that felt by the artists. My appreciation and understanding did feel enhanced by my ability to interact both visually and physically with the work. One sample swatch quickly became my favorite to interact with — a deep blue thermochromic agar bioplastic that, as thermo suggests, would transform to a lighter blue whenever heat was applied to the surface.

Thermochromic Agar Bioplastic swatch by Fiona Bell. Photograph by Ava Marr.

My excitement for this unique and exquisite material was shared with anyone who happened to walk by my table, such as Dr. Andrea Polli, who had matched my excitement for the color-changing blue tones. She began examining the identification tab stapled to the swatch to analyze the recipe and seemingly nodded her head in approval at the list of ingredients unbeknownst to me. This prompted me to ask if she was involved with the sciences as she seemed familiar with the formula. She introduced herself to me as a faculty member at the university and, upon personally looking into her position further, she is a distinguished researcher in the field of bio-art. Dr. Polli also identified her work as a collaborator in the exhibition and provided some clarifying information regarding her pieces, while additionally mentioning the future possibilities related to the combination of the arts and the sciences. I shared with her that I was studying art history as an undergraduate and was absolutely in awe in with the intermixtures of the two academic disciplines that were presented in the exhibitions, mentioning that I had an interest in writing about the opening. Like our excitement shared over the thermochromic swatch, I felt we additionally had a shared excitement in the rise of bio-art from the academic perspective and I thanked Dr. Polli for spending some of her time speaking with me.

After my conversation with Dr. Polli and some more entertainment provided via the swatches, opening remarks were set to start. Remarks were provided by UNMAM Director Arif Khan and Curator of Prints & Photographs Mary Statzer, which allowed for a more contextual understanding behind the various artistic processes as well as the arrangement of the show. Additionally, museum staff were recognized for their efforts in installing and developing the exhibitions. Dr. Fiona Bell and Polli were identified during the remarks, as well as the other artists who had contributed to the exhibitions that I did not have the pleasure of meeting.

Installation shot of Notes on Care featuring works by Rachel Cox. Photograph by Stefan Jennings Batista.

Following the remarks, I removed myself from the bio-swatches and began stepping towards the back of the gallery. To the right and up a flight of stairs sat the entrance to the Coke Gallery containing Cox’s Notes on Care. Like Hindsight Insight 5.0, Cox relays her work to themes surrounding bio-art and the microscopic album but from the perspective of an extremely personal journey. Cox was able to document her fertility treatments with emotional photographs that reveal the artist’s vulnerability. Her masterful photographic techniques can be witnessed through the application of varying forms of presentation, relying mostly on black and white contrast. Following the broader themes of Hindsight Insight 5.0, three microscopic photographs were displayed in the Coke Gallery, the photographs were of Cox’s embryos as she underwent IVF treatment, with two non-viable and one viable. These images, taken by a lab technician, have been reworked by Cox for ownership and are directly related to the photo album by Richmond. Cox makes note that viability is often determined via photographic analysis of a microscopic image, and she questioned the reliance that is placed on this method as she has encountered many photographic misperceptions in her career. The moving feature of Notes on Care and my recommending reason for visiting this space is due to both the emotional impact of the viewing as well as the much-needed education that is provided in relation to reproductive and fertility treatment, a commonality in the lives of Western women that has been historically silenced in conversations. Cox allows for her experience to be perceived which thus allows others to personally relate in a way they may have never been able to.

Arif Khan, UNMAM Director (LEFT), view a projection created by Bryan Konesfky, Director of Basement Films (RIGHT). Photograph by Aziza Murray.

Once I felt I had processed the emotions that came with Notes on Care, I sauntered back into the Main Gallery and felt called to view the pop-up display put on the Basement Films group. I ascended in the elevator to the Upper Gallery and entered the room immediately to the left. I discovered their crew running several projectors that crossed over one another, with two projectionists that were running black and white shorts while the third operated an homage to Elias Romero. Brian Konefsky, the third projectionist and Director of Basement Films, explained that Romero would suspend assorted objects in a water-and-oil solution while letting a light prism conduct the movement of color. The technique dates to the mid-20th century and can be seen within the visuals for performances by groups like Jefferson Airplane. The connection between this technique and its correlation to bio-art can be reasoned by the case that Romero would create visually stimulating pieces utilizing new-wave technology.

SCOBY Breastplate (LEFT) and Living Kombucha SCOBY Cultures (RIGHT) by Fiona Bell. Photograph by Ava Marr.

About an hour remained until the opening would conclude. At this point, the attendance had dwindled down, but the energy was still lively. Upon debating where I would go next, or if it was my time to depart, I found myself locking eyes with Dr. Bell and was welcomed to engage in a dialogue with her. Letting her know how interesting I found her work, I asked the ever-so-vague question of what her favorite piece was, before immediately admitting that may have been the worst question one could ask an artist. After a little chuckle, she admitted love for her SCOBY breastplate, a piece that I have yet to address but is truly distinctive. Paired near the breastplate are jars with active kombucha fermentation occurring; the jars, Dr. Bell explained, would be skimmed from the top to harvest the goopy SCOBY material, which she would then mold while wet onto the bodice of a feminine figure before it set to dry. Within the textile work were a string of lights embedded in activated charcoal that reacted to touch, another interactive feature within the exhibition. 3-D printed vessels, which are attributed to her postdoctoral research, were across the gallery and discussed as well. Her enthusiasm and willingness to divulge the creative process of her work is something I reflect on with gratitude, a similar gratitude I felt when Dr. Polli shared her process with me.

With retrospect to my education and experiences this Fall semester, I see that my perspective towards bio-art has shifted to recognize that this field has been under development for some time and is evolving into a contemporary practice. The University of New Mexico Art Museum is taking initiative in the field by providing as well as encouraging education and experimentation in bio-art, collaborating with leaders and researchers in this medium at the University. Roots as suggested by the museum can be seen in the innovative album compiled by Richmond (even if he may not have seen the artistic connections in his chemistry documentation himself.) The inspiring text posed questions surrounding the complexity of life and the scientific evolution of art to the collaborators of the exhibition. Exciting movements in bio-art can be highlighted by the introduction of biodegradable and sustainable materials as well as methodological practices that can provide inclusive opportunities involving many disciplines as the arts and sciences continue to evolve.